My son David recently rediscovered a paper he wrote in college comparing King Arthur of Great Britain and King Gesar of Ling in Central Asia. We had several conversations at the time and since then we have had more discussions about the way these two legends helped guide and mold their respective civilizations. Many of our discussions occurred during the years I was writing Windhorse Warrior, a novel about Eastern Tibet during the Chinese Communist invasion and occupation. In my novel the story of King Gesar inspires a small group of people to create a socioeconomic structure based on Buddhist and true Communist principles that would provide an alternative to what was being forced upon the Tibetan people. Besides promoting my novel I hope this, and following posts, can help the West discover and understand King Gesar and the East, King Arthur.

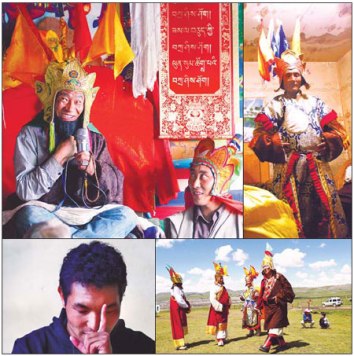

The legend of King Gesar is an orally transmitted epic poem. The verse of the songs and opera performances were not written down until the late 19th or early 20th Centuries. The legend still has significance among Tibetans, both in exile and those still in Tibet, and among the people of Mongolia, Tuva, Buryatia, Kalmyk and other Buddhist groups in Central Asia. The story is kept ‘alive’ by bards who enter a shamanic trance, visit Gesar’s time and place, the Kingdom of Ling, and recite the legend from first-hand experience. The female or male bard observes and gives voice to the activities of Gesar and his warriors and courtiers in their separate reality though at the present moment. In this way the story deepens and evolves with each bardic visitor. Each one sees and understands some unique part of the mythic motif of ‘once upon a time, far, far away’ which magically unifies the present with the past and future, the eternal now.

The legend of King Gesar is an orally transmitted epic poem. The verse of the songs and opera performances were not written down until the late 19th or early 20th Centuries. The legend still has significance among Tibetans, both in exile and those still in Tibet, and among the people of Mongolia, Tuva, Buryatia, Kalmyk and other Buddhist groups in Central Asia. The story is kept ‘alive’ by bards who enter a shamanic trance, visit Gesar’s time and place, the Kingdom of Ling, and recite the legend from first-hand experience. The female or male bard observes and gives voice to the activities of Gesar and his warriors and courtiers in their separate reality though at the present moment. In this way the story deepens and evolves with each bardic visitor. Each one sees and understands some unique part of the mythic motif of ‘once upon a time, far, far away’ which magically unifies the present with the past and future, the eternal now.

Literary accounts of King Arthur began before the 9th Century but it is likely these were preceded by an oral tradition transmitted from generation to generation and place to place by Celtic bards and perhaps the Druids themselves who kept ‘alive’ a legend of a warrior king who embodied their highest ideals. We might assume that they did so in the same way as the shamanic bards of Central Asia: by ‘spirit journeys’ into a parallel world. We can assume this because shamanic methods of spirit journey are universal and thousands of years old.

There are Celtic mythological roots to stories of Arthur and Merlin throughout Britain, Wales, Ireland and Britany including tales of Merlin involved in the creation of Stonehenge. If so, these stories go back at least 4000 or 5000 years. The Celts developed an extensive empire that, by 200 BC, reached across Britain, northern France and into the Italian peninsula. They were eventually conquered by the Romans in the 1st Century BC. This began a period of Roman and Christian influence over the Celtic culture.

There are Celtic mythological roots to stories of Arthur and Merlin throughout Britain, Wales, Ireland and Britany including tales of Merlin involved in the creation of Stonehenge. If so, these stories go back at least 4000 or 5000 years. The Celts developed an extensive empire that, by 200 BC, reached across Britain, northern France and into the Italian peninsula. They were eventually conquered by the Romans in the 1st Century BC. This began a period of Roman and Christian influence over the Celtic culture.

Historians believe there never was a British king named Arthur but his name first appears in an account of British history written by Nennius, a 9th Century monk. He wrote of King Arthur as victorious over the Roman empire in the 2nd Century BC while also waging a 5th Century war on the Saxons. The name Arthur appears in this account because Nennius needed “the Welsh-sounding name to add focus to what was principally a political treatise” (Scott-Robinson). By using the name of a well know mythological hero of Welsh epic poetry, Nennius added deep significance to his fanciful history. In the 12th Century Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote a ‘History of the Kings of Britain’ and further embellished Nennius’ account. This book “owes a great deal to Geoffrey’s fertile imagination” (Scott-Robinson).

Thus an earlier bardic legend of Arthur, a heroic war leader, was co-opted and modified to fit political intentions and contemporary cultural values. By the time novels were written and printed for the literate noble class in the 15th Century, Arthur had become more of a figurehead while the real action of the stories centered on his knights. Western civilization was changing; the individual began to take center stage rather than the collective represented by the King.

By this time, too, creative imagination was the novelist’s tool instead of shamanic spiritual journey. The modern writer imagines his or her own world and shares it with the reader or audience through text or screen. Culturally popular stories such as Star Wars, the Lord of the Rings, Narnia or Harry Potter evoke an alternative world ‘in a galaxy far, far away’ or just through the wardrobe. A good writer or director enables us to participate in other worlds of the imagination but seldom enter, like a shamanic bard, the “zone unknown,” as Joseph Campbell called it. Gifted writers, nevertheless, if they are open to the muse, can tap into mythic truth* and a good listener can participate in the imaginative journey ‘further in and higher up’ into Narnia.

Over the past seven to five hundred years, the ability to have direct access to deeper realms of spiritual insight has faded away from industrializing societies. The result is that today stories of King Arthur are nearly unrecognizable as a spiritually or socially uplifting saga. For example, a recent movie about King Arthur (http://kingarthurmovie.com) is an action film presenting a tumultuous Camelot with characters mirroring the violent, competitive, self-serving values of our patristic system. There remains not a shred of the ideal good king who created an ‘enlightened society’ in which all the people could thrive. As the global ‘babylon’ of self-centered consumerism continues to expand its reach, the legend of King Arthur will continue to succumb to this erosion. And even the legend of King Gesar, as it catches on and is translated into Communist Chinese culture, will experience a similar erosion.

I have some questions that are open to discussion: If these old epic legends are the result of spiritual journeys, how do shamanic bards tapped into the same inner landscapes, heroic personalities, and events? Are Camelot and Ling actual places in a parallel world? Or is it the power of suggestions; one bard follows another’s lead in describing the place and events? And what about the modern novelist or screenwriter; would their stories about Camelot differ from what we are given to read and watch now if they could cross into that parallel world through shamanic trance?

Shamans held places of importance in early societies. In many places in the world today she or he is someone who walks with one foot in the everyday world and the other foot in the spirit world. Epic legends, including Arthur’s and Gesar’s, are told by shaman to remind the community that all life is a manifestation of a greater Reality. They remind people that they are interdependent and filled with the capacity to know Reality directly. They guide the community in the ethic of universal justice and compassion toward all beings. Both King Arthur and King Gesar manifested what it is to be fully human; fully awakened, compassionate beings.

I am exploring these two legends because I feel it is important that we maintain contact with the spiritual insights of the ancients. The legend of Gesar, and most likely the early oral accounts of Arthur, carry values and wisdom teachings that go back over 50,000 years into our past and, as the protagonists in Windhorse Warrior discover, the Legend of King Gesar holds a key to helping us establish an ‘enlightened society’ and overcome our current environmental and social crises.

__________

Quotes from:’ The Old Religion of Britain, Weird Tales from the Middle Ages,’ Richard Scott-Robinson: http://www.eleusinianm.co.uk/Arthur/wt1arthur.html

Other resource: The Epic of Gesar of Ling: Gesar’s Magical Birth, Early Years, and Coronation as King, translated by Robin Kornman, Sangye Khandro, and Lama Chonam, 2015

*If ‘mythic truth’ strikes you as an oxymoron you have clearly been duped by the current cultural system that is out of touch with ancient wisdom. A ‘myth’ is not a fantasy nor is it a false belief. Used in the sense of this article, it refers to archetypal stories that communicate universal facts about our selves and our world.

Soosi Day

/ February 5, 2018I thoroughly enjoyed this Richard. It stimulated the Ancient lit teacher in me. I have a children’s book about the Tibetan king that was given to my by our Tibetan friend, Jimpa. I would love to have a print copy of this WordPress. Can you coach me on how to do that?

LikeLike

Rishi

/ February 5, 2018Thanks, Soosi. To have a print copy, put it into Reader view and select the whole article, including pictures. Then past it to a Word doc or Pages. Edit out extra spaces and extra stuff that might have been copied too and print.

LikeLike

gary cox

/ May 17, 2018okay 6:44 :-)

>

LikeLike

Tanya Joyce

/ July 20, 2020Very glad to see this. I, too, have seen many parallels between Gesar and Arthur. Poems like “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” and “The Pearl”, plus Chaucer, started me off in that direction and I came to Gesar while looking at mythology from the Caucasus. Recommending John Colarusso for mythology from the Caucasus and John and Catlin Matthews for all things Arthurian. All 3 of these people work with mythology, history, and multiple languages and traditions.

LikeLike