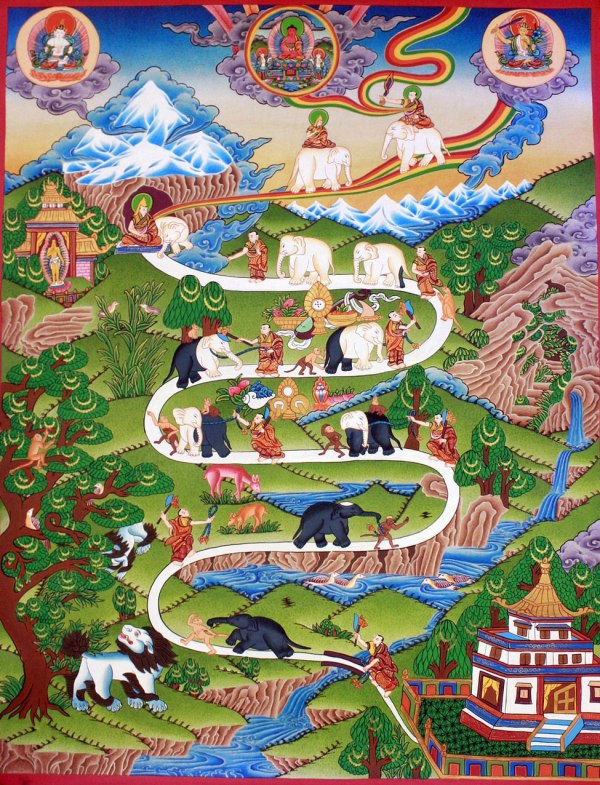

Shamatha, which means calm, is the practice of meditation to develop the ability to focus the mind in single-pointed concentration. This is practiced as a pre-requisite for mindfulness or insight meditations. In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition this practices is described as a nine stage progression beautifully depicted in this thangka showing a monk chasing and finally capturing an elephant.  The elephant is being led by a monkey. The monkey represents distractions. How well we know this scenario! This is ordinary mind or conventional mind mired in the Babylon Matrix (Jonathan Zap). But through study of the writings of Wisdom Teachers and mediation practice, the monk is able to capture and subdue the elephant. Gradually both the monkey and the elephant turn white representing the meditator’s ability to maintain the power of concentration.

The elephant is being led by a monkey. The monkey represents distractions. How well we know this scenario! This is ordinary mind or conventional mind mired in the Babylon Matrix (Jonathan Zap). But through study of the writings of Wisdom Teachers and mediation practice, the monk is able to capture and subdue the elephant. Gradually both the monkey and the elephant turn white representing the meditator’s ability to maintain the power of concentration.

Stages three and four represents the meditator’s ability to fix and hold his or her concentration steady. The meditator has lassoed the elephant and gradually the monkey, elephant and even a rabbit turn and look at the meditator to indicate that distractions acknowledge who is in charge.

In stages five and six the meditator begins to lead the elephant and the monkey of distraction follows the mind rather than leading it. The mind is controlled; the meditator uses a goad to discipline the elephant. The rabbit disappears and the mind is finally pacified.

In the seventh stage the monkey leaves the elephant and stands behind the meditator and pays homage. In stage eight the meditator is in complete control. Single-pointed concentration is achieved.

The ninth is the stage of mental absorption. Perfect equanimity is found and the path has ended. The elephant rests beside the meditator who sits at ease. Now out of the meditator’s heart streams a rainbow like ray.

Stages ten and eleven represent crossing over into mental bliss. The meditator rides the elephant along the rainbow path into the perfection of the transcendent realm and returns bearing the sword of Wisdom. Samsara’s root is severed by the union of shamatha and vipashyana or insight meditation with emptiness as the object of contemplation. Aware of pure awareness, the meditator is now equipped with Compassion and Wisdom to guide others on the path to enlightenment.  In the Chinese Chan (Zen) tradition this concept is illustrated through the Ten Ox Herding images by Master Kakuan in 12th Century China. There is a similar progression to the pictures to depict levels of realization.

In the Chinese Chan (Zen) tradition this concept is illustrated through the Ten Ox Herding images by Master Kakuan in 12th Century China. There is a similar progression to the pictures to depict levels of realization.

The meditator (1) searches for the ox, (2) sees the tracks and follows them until (3) the ox is discovered in its hiding place. Once the ox is captured (4), the meditator is able to lead (5) and (6) then ride it back home. (7) Once home, the meditator achieves perfect concentration in non-duality (8). The next step, according to the Chan tradition is to realize the underlying, unshakeable unity of the cosmos (9); there is no separation between created (samsara) and uncreated reality (nirvana). Once realized, (10) the meditator returns to the marketplace. His Compassion compels him to help others on the path to enlightenment by offering his Wisdom.

The difference between the Tibetan and Chan illustrations reflects the cultural orientations of each rather than significant differences in the path or outcome. The Tibetan thangka, a sacred painting on cloth, is colorful and highly mythological while the Chan has an earthy pastoral flavor. Of course, there are no elephants in Tibet – nor in China – but Tibetan Buddhism was highly influenced by Indian culture. The Ox Herding pictures on the other hand demonstrate the Chinese orientation to nature beautifully and simply represented in ink drawings.

Both of these are examples of sacred or visionary art created for the purpose of teaching or clarifying the path of spiritual development. (See previous post: The Mission of Art.) Sacred art is purposeful and often uses high levels of logic as it in these illustrations. At the same time it is visionary and uses archetypal images from the realm of myth. Sacred art at its best is a union of logos and mythos.